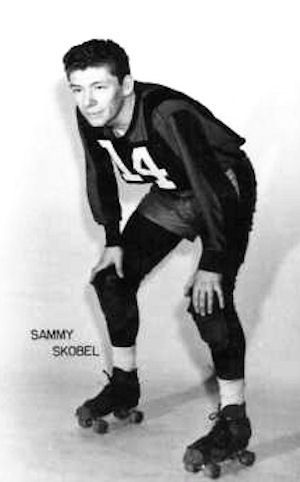

Samuel “Sammy” Skobel was an American roller derby skating star who opened a hot dog restaurant in Mount Prospect after his retirement from his sport.

Legally blind, Skobel was a derby star who was voted most valuable player in the league three times and inducted to the Roller Derby Hall of Fame in 1953. Skobel also held the world record for the fastest mile skated on a banked track – accomplished in 1958.

Sammy was born to Russian immigrants on April 26, 1926. His parents owned a grocery and meat market on Chicago’s Maxwell Street.

An infection with scarlet fever at the age of four left him legally blind, with less than ten percent of his vision remaining.

A track star at Crane Technical High School, he ran a 4:22 mile and was offered full scholarships to three universities, but those offers were rescinded when the schools learned he was legally blind. He had a hard time finding and maintaining a job after graduating from high school. In fact, he was denied a job in an electronics factory and got fired from a job repairing innertubes after just a few hours.

In 1945, Skobel tried out for the roller derby at the Chicago Coliseum but was rejected after the general manager of the Roller Derby watched him struggle to fill out the application with a magnifying glass. Instead, Skobel joined the roller derby working as a locker attendant, earning 50 cents per day.[ He worked in the center of the banked-track ring, memorizing the styles and outlines of the skaters. When he heard that the derby was holding tryouts in Chattanooga in January 1946, he traveled there by bus and was able to keep his low vision a secret during trials. He signed with the Brooklyn Red Devils in 1946, keeping his disability a secret for the first five years he played. Skobel would listen for the sound of an opponent’s skates coming up behind him, and if a skater was close he could see whether they were wearing stripes or certain colors.

In 1949, Skobel became the youngest team captain in the history of the sport. Skobel was traded to the Chicago Westerners in 1953, where he skated for twelve seasons. He skated for the IRDL Midwest Pioneers from 1964 to 1966. He had several nicknames throughout his career, including “Slammin'” Sammy Skobel and “Gunner” Skobel.

Skobel was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player of the year three times during his skating career and was on 18 all-star teams. He was one of the first seven people inducted to the original Roller Derby Hall of Fame in 1953 and in 1958 set a world record fastest mile on a banked track, skating the mile in 2 minutes and 36 seconds.

By the end of his career, he was paid $80,000 each season. He skated his last game in May 1966, but would later serve as a consulting coach for the San Francisco Bay Bombers.

Skobel married his wife Acrivie (“Vee”) in 1952. They had two sons together, Sam Jr. and Stephen.

After retiring from the roller derby, he opened Sammy Skobel’s Hot Dogs Plus in downtown Mount Prospect. He ran the restaurant from 1965 to 1989, when he sold it to a former employee. He also traveled as a motivational speaker, giving talks on “Creating a Positive Attitude for Life,” and advocated for other blind athletes. For instance, in 1971 he helped found the American Blind Skiing Foundation.

In 1982, Skobel collaborated with a freelance writer to write his autobiography, titled Semka. The jacket described the book as the “story of a determined young blind man from his boyhood in Chicago’s Maxwell Street to a professional athletic career, setting a world speed skating record.”

Skobel died on June 9, 2018 at age of 92 in his home in Mount Prospect.